Exclusive: Darwin Nunez, one of the most exciting strikers in international football, was raised in a difficult environment in Uruguay before joining Liverpool.

The massive £85 million addition to Liverpool Darwin Nunez has already accomplished his greatest life ambition.

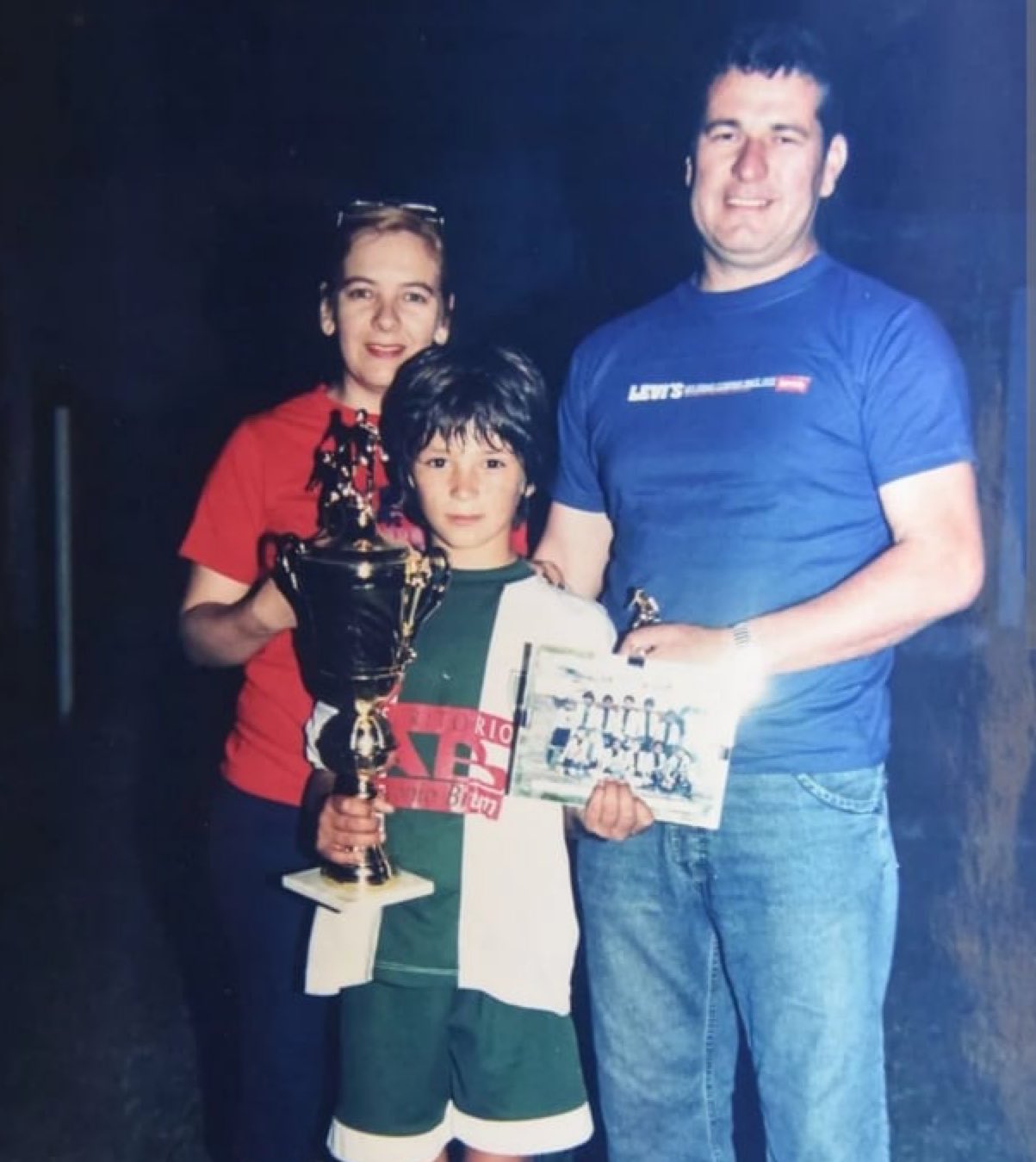

The 22-year-old striker from Uruguay used to dream of being good enough to one day give his parents a new house when he was playing soccer with his friends in the streets of Artigas, a city in the northeast of the nation near the Brazilian border.

The little home that Nunez shared with his parents, dad Bibiano, mother Silvia Ribeiro, and older brother Junior was situated on the Cuareim River’s flood plain, meaning that the few pieces of furniture they did have would frequently behed away.

Nunez has always felt that his purpose in life is to care for the individuals who gave up all to enable him to leave the poverty into which he was born. Nunez states, “I never forget where I come from.” “My family is modest and hardworking. Even after working eight or nine hours a day as a laborer on a construction site, my father would still attempt to find money to purchase me football boots even if his shoes were falling off.

“My mother was a homemaker. However, she strolled about the town’s streets gathering empty bottles to resell to the shops. Our Artigas home was never in excellent shape due to the frequent flooding. When I started playing football, my first idea was to start a business and purchase my parents a house. That was my intention. My parents provided everything for me, so I’ve continued to put in a lot of effort to win their approval. It feels as though I’m returning the favor for all of their love and support.

“A father’s love is unique,” Nunez continued. I learned from my dad that material things are not everything in life. Indeed, I frequently slept with an empty stomach. However, my mother was the only one in the home to sleep with the emptiest stomach. A mother dedicates her entire life to her children. My mother wanted to feed the rest of us, so she frequently went to bed at night without eating.

“Even though I grew up in a low-income neighborhood, I am proud of my background. I discovered there how crucial it is to communicate things. My buddies and I used to bring snacks or candies so that we could share them when we were together. They used to provide us food, so I used to get up early to go to school. My mother wasn’t home when I got out of school at 3 p.m., so I would go directly to training. She was out and about gathering bottles.

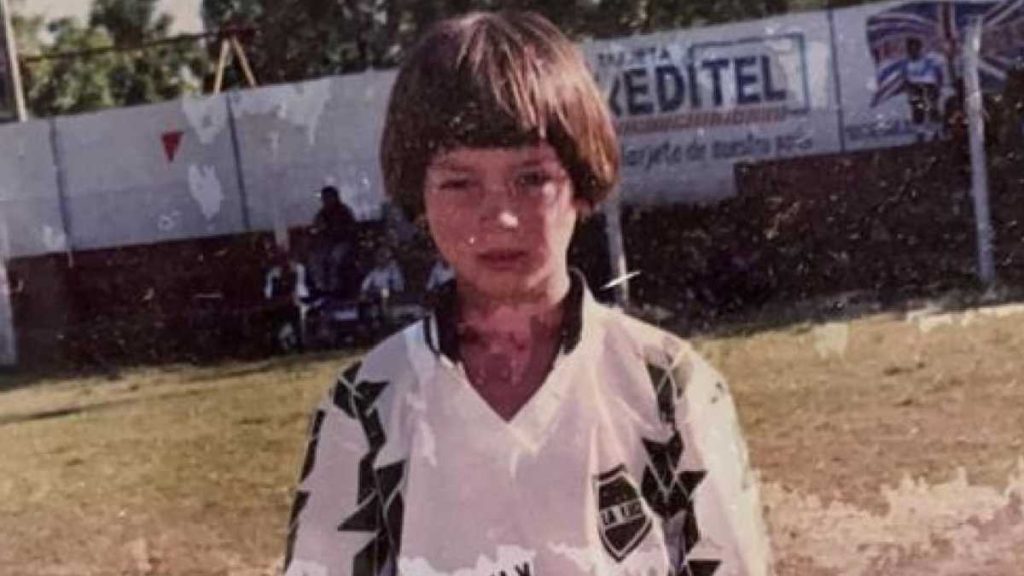

After being discovered by a Penarol scout, Nunez traveled 370 kilometers to attend the club’s academy in Montevideo at the age of 14. Brother Junior, who was also under Penarol’s supervision, had just begun working out with the first team when he had to halt his nascent career to come back to Artigas for assistance regarding a family crisis. Junior persuaded the child to pursue their aspirations together and declined to take his sister with him.

Nunez did not have an easy journey to the top. After playing through discomfort to make his senior debut, he had to have surgery again at the age of 16 to repair damage to his knee ligaments. He remembers, “I gritted my teeth to play even though my knee hurt.” “I came off the pitch crying at the end of the game, but the medics said it was in my head,” the player said. This time, they had to operate on my patella. Once more, there was a great deal of pain.

In 2014, Nunez relocated to Europe and signed a contract with the Spanish team Almeria. A season later, Portuguese powerhouse Benfica paid £20.5 million to sign him. He would ultimately become the record acquisition for Liverpool, having cost the club £64.2 million in addition to an additional £25 million in add-ons. However, questions have frequently dogged his meteoric ascension. While representing Uruguay at the Under-20 World Cup in Poland, Nunez was the subject of social media trolls, forcing him to seek psychological assistance.

He gave the following explanation: “I used to browse the (social media) networks frequently, but I started to see offensive remarks. I was genuinely made ill by them. I needed to talk to Axel Ocampo, the national team psychologist, since the criticism was starting to get to me. He was a great assistance to me, but the solution was easy. I no longer check my phone in the changing room to see what others are saying about me. I use my phone to communicate with my loved ones just after games. I’ll only pay attention to those who have shown support.